During the six-hour drive from New York City to a tiny town in northern

Vermont, Iranian student Shirin Estahbanati cried at the thought of

seeing her father for the first time in nearly three years. Since then,

he had suffered a heart attack, and she hadn’t dared leave America to

comfort him.

But as she traveled north, she also couldn’t stop worrying. What if she

missed the turnoff and drove across the U.S.-Canadian border by mistake?

Estahbanati, like many Iranian students in the United States, has a

single-entry visa and can’t leave the country without risking that she

won’t be allowed back in. And her parents, as Iranian citizens, are

blocked by U.S. President Donald Trump’s travel ban from visiting her in

the United States.

She didn’t want to miss her destination: the Haskell Free Library and Opera House.

Estahbanati and her family had agreed to meet around 9 a.m. at the

library, which through a historic anomaly straddles the U.S.-Canada

border – and today has been thrust into an unlikely role as the site of

emotional reunions between people separated by the administration’s

immigration policies.

The 31-year-old parked her car and, excitement battling with anxiety,

walked to the entrance of the Victorian building. But two hours later,

her parents and sister still had not appeared from the Canadian side,

and her calls to her sister’s cell phone went unanswered.

Finally, she saw them. Because of construction near the library, their

GPS device had sent them to the line for the U.S. port of entry. Her

parents had no U.S. visas, and they had been detained by American border

agents. After approximately two hours, they were released and allowed

to join Estahbanati at the library.

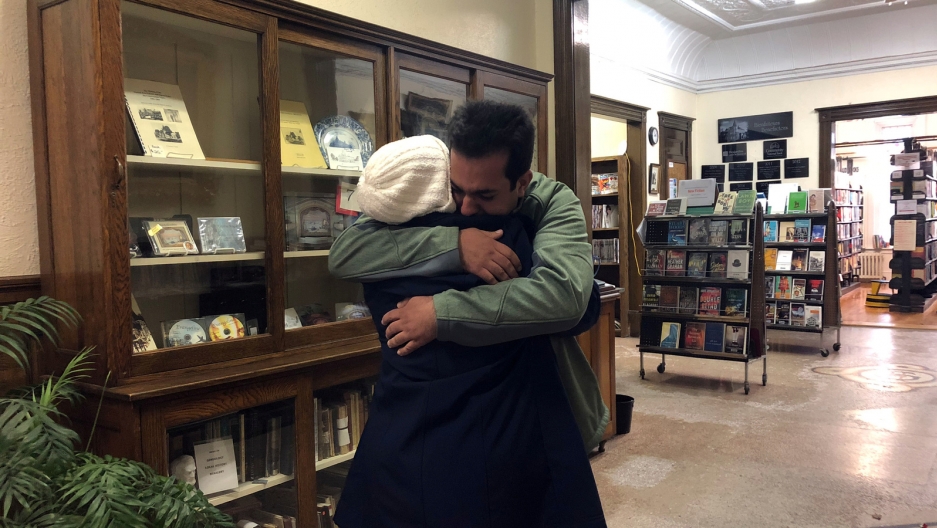

When they hugged each other, it felt as if her father had shrunk. He

took a deep breath as he held his daughter tight. “I missed your smell,”

he told her.

Remembering the moment, her smile turned down with the effort not to cry. “The time I was just hugging my parents,” she said, “I was thinking, I wish I could stop all clocks all over the world.”

This year, as migrant families from Latin America were separated at the U.S. southern border, a more nuanced reality has been playing out on the northern frontier with Canada. Here, dozens of Iranian families have reunited at the Haskell library. Drawn by word-of-mouth and a smattering of social media posts, they have come to the geopolitical gray zone at the rural frontier library, located at once in Derby Line, Vermont, and Stanstead, Quebec.

The Iranian families have undertaken fraught, costly journeys for the chance of a few hours together on the library’s grounds. Although several Iranians said they hadn’t faced any obstacles from immigration authorities, others said U.S. border officers have at times detained them for several hours, tried to bar them from entering the library, told them they shouldn’t be visiting each other there or said they should limit their visits to just a few minutes. American and Canadian officials have threatened to shut the library over the visits, one library staff member said.

“This is a neutral area, but the U.S. government doesn’t accept this situation, and they put a lot of pressure on us,” said Sina Dadsetan, an Iranian living in Canada who traveled to the library to see his sister the same day Estahbanati saw her family.

The Trump administration says its travel ban is necessary to protect the United States, arguing that the countries in question – Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Yemen and, to a lesser extent, Venezuela – don’t share enough information that would confirm their citizens are not a threat, or are the source of terrorism threats.

Officials with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which oversees the Border Patrol, declined a request for an interview about the library. A spokesman, Michael McCarthy, declined to comment on the families’ accounts of their interactions with U.S. border officials or on the library staff member’s allegation that U.S. and Canadian authorities have threatened to close it.

“U.S. Border Patrol works closely with our Canadian counterparts, as well as the local community, to prevent illegal cross border activity,” McCarthy said in a statement.

Erique Gasse, a spokesman for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canada’s federal law enforcement agency, denied that the agency had threatened to shut the library down. “This is not the way we talk,” he said. “We don’t do that.”

He insisted the RCMP doesn’t patrol the area regularly and only goes there when called. “We don’t have any problem with the library,” he said.

Mahsa Izadmehr, an Iranian doctoral student in engineering at the University of Illinois-Chicago, had gone seven years without seeing her younger sister, who lives in Switzerland. In late September, they met at the library.

But as they approached each other at the border, demarcated outside the library by a line of flower pots, a U.S. Border Patrol agent quickly got out of a car parked close by.

“He said, ‘It’s been about a month that we’ve closed this; we don’t allow anyone to meet here,’” Izadmehr said. “I asked him, ‘Can you at least give me permission to hug my sister?’”

The agent allowed them to embrace but barred them from exchanging the gifts they had brought – dresses, Swiss chocolates and a watch – and kept a close eye on them as they talked from opposite sides of the flower pots.

The sisters finally entered the library when a staff member offered them a tour, but Border Patrol agents later chastised the staff member, said Izadmehr, who witnessed the exchange. McCarthy declined to comment on the incident.

Richard Creaser, chairman of the Derby Line village trustees, said he understands why the family visits would be a “point of tension” for Border Patrol officials, because the Iranians have to walk onto American soil to enter.

“I could see where that would be an issue,” Creaser said.

The Supreme Court upheld Trump’s travel ban this summer after a lengthy legal battle. Of the people affected by the ban, it is by far Iranians who study most frequently in the United States and who tend to be middle class and can afford international travel.

Several Iranians told Reuters they’ve also met in recent months at Peace Arch park, located at once in Washington state and British Columbia, on the western coast of North America. But for families with members in major eastern cities, the cost of crossing the continent can be prohibitive, leaving the Haskell library as their only choice.

Even so, Sina Dadsetan and his sister estimated their family spent more than $1,600 on their two-day reunion at Haskell, not including their parents’ air travel from Iran, for what would be approximately 10 hours together.

The library is vulnerable to pressure from authorities because although the building sits on American and Canadian land, its entrance is on the U.S. side. U.S. officials allow staff and visitors from Canada to walk a few yards onto American soil without going through an official port of entry.

“Often there’s altercations with either RCMP or (U.S.) border security,” head librarian Joel Kerr said in a brief interview in early November, on a day in which two Iranian families reunited at the library. “They mostly harass us and threaten to shut us down.”

Kerr, who started in his position in October, said he couldn’t provide any details of how the agencies had threatened to shut down the library. Members of the library’s board of trustees, which recently issued a policy barring the visits, either did not respond to requests for comment or declined to comment at length.

The library is a relic of a time when Americans and Canadians, residents say, could cross the border with simply a nod and a wave at border agents. It was the gift of a local family in the early 1900s to serve the nearby Canadian and American communities.

“What we are so proud of is that we do have a library that is accessed by one single door,” said Susan Granfors, a former library board member. “You don’t need your passport. You park on your side, I’ll park on my side, but we’re all going to walk in the same door.”

But after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, the northern border hardened, and the law enforcement presence in the area is immediately visible. And in September, a Canadian man was sentenced to 51 months in prison for smuggling more than 100 guns into Canada, some of them through the Haskell library.

Still, inside the building itself – decorated with wood paneling, stained-glass windows and, on the Canadian side, a moose head – the old ways mostly prevail. Patrons and staff freely cross the international boundary, marked with a thin, flaking black line extending across the brightly decorated children’s reading room and the main hallway.

On the morning of Aug. 14, Estahbanati parked her car in the library’s small lot and walked to its gray granite entrance. That’s where she encountered Sina Dadsetan and his parents around 11 a.m., when they arrived at the library for their own reunion with his sister Saba, an Iranian student living in Pennsylvania.

As the Dadsetan family approached the library from the opposite sides of the border, Estahbanati, in tears, asked them if they had seen her family. They had not.

But when the Estahbanatis, too, had finally reunited, it was not the end of the families’ problems that day. Nearby construction had cut off water to the library, and it was unexpectedly closed. A library staff member had given the families written permission to meet on its grounds, but Border Patrol agents objected to their meeting there.

“It was really stressful, because I just wanted to be with my parents,” Estahbanati said. She pleaded with the agents, and they relented, allowing them to meet outside the library for 20 minutes. That 20 minutes passed, and though the agents watched from close by, they allowed the families to meet for several hours that day.

On the second day the Estahbanatis and Dadsetans met at the library, at least two other Iranian families were also there, they said. Several of the mothers had cooked elaborate Iranian dishes for their children to enjoy.

Estahbanati had asked her mother to make her childhood favorite, a crunchy, layered rice dish called tahchin. Her mother had even brought some saffron from Iran to use in the dish.

“She was happy that she can cook for me,” Estahbanati said, “and I was glad that I could have that food that my mother had made herself.”

It is difficult to know exactly how many families have reunited at the library, but a signature book near the front entrance shows around 12 obviously Iranian names between March and November. Reuters identified seven other families, all Iranian, who had visited the library or tried to do so this year.

People with a close connection to the library were reluctant to speak about the visits, worried that publicizing them would draw more families, attract more pressure from authorities, or both.

“We are trying to be very neutral,” Patricia Hunt, a current board member, said in a brief phone interview. She declined to comment further.

Kerr, the librarian, said he planned to hold a meeting between library officials and both countries’ authorities to draw up a plan to deal with the visits.

“We don’t want to put a stop to it, necessarily, but we need to somehow control it in order for us to stay open,” Kerr said. “It’s basically only tolerated by both sides, because technically, it shouldn’t really be allowed.”

On a Saturday in early November, two Iranian families met at the library, chatting quietly in its two reading rooms. The normal business of the library continued amid the tearful reunions and goodbyes in its corners: Parents and children streamed in and out to return books and browse the stacks. Teenagers accessed the internet on library computers and leafed through its DVD collection.

The Iranians were mostly oblivious to signs stating in English and French that, by order of the library’s board of trustees, “family gatherings are not permitted.” Kerr said the signs had gone up just the week before.

Comments

Post a Comment